John Pierce AO

Presented to the Australian Institute of Energy and Griffith University, 18 July 2019, Brisbane Australia

Download a PDF version of this speech

***

In Australia we have a very open and accessible set of arrangements to change regulatory frameworks in response to policy changes or structural change in the energy industry. Any person or organisation can propose a change to the rules – from private citizens, business and government. The Australian Energy Market Commission depends on the insights and views of our stakeholders to help inform our thinking and challenge our proposals for reform. Continuous dialogue is one of our key commitments. We have an obligation to evaluate all rule change requests against statutory objectives which require us to serve the long term interests of consumers.

The energy system is being transformed and we are changing the market from top to bottom. Given the amount of change occurring the Commission has articulated a set of five rule-making priorities which will help make it possible for stakeholders to contribute more effectively to energy market developments and influence our provision of strategic advice to governments. Those five priority areas of reform are generator access and transmission pricing; system security; integrating distributed energy resources; digitalisation of energy supply; and reliability.

Introduction

A proper discussion of this topic, even it was to be confined to the electricity sector, would demand something like an extended essay or a book. Given the time we have today, that’s obviously not going to happen. So I will confine myself to a few key points, sprinkled with some carefully selected historical and personal anecdotes to help keep you interested.

In May 1986, the NSW government was presented with the final report of an inquiry led by Gavan McDonell. The background that gave rise to the inquiry was in some respects the opposite of the concerns that many have today, yet in other respects remarkably similar.

There was an excess supply of generation capacity and the organisation responsible for bulk supply, the Electricity Commission of NSW, wanted to build more. The report’s finding, in a nutshell, was that the Electricity Commission of NSW needed to plan better and it made recommendations about how to go about this. As well as cancelling plans for the construction of an additional four by 660 MW power station that was on the books at the time – a sister station to Eraring and Bayswater.

That excess supply and the possibility of more, was a problem in my view because of the consequences that flowed as a result of the institutional, regulatory and industry structures that existed at the time.

For the economy generally, having a few billion dollars of capital sitting around not doing much was a problem in itself when arguably those resources could well have been of more use doing something that people actually wanted. But the truth is that costs of this nature tend to be not readily observable.

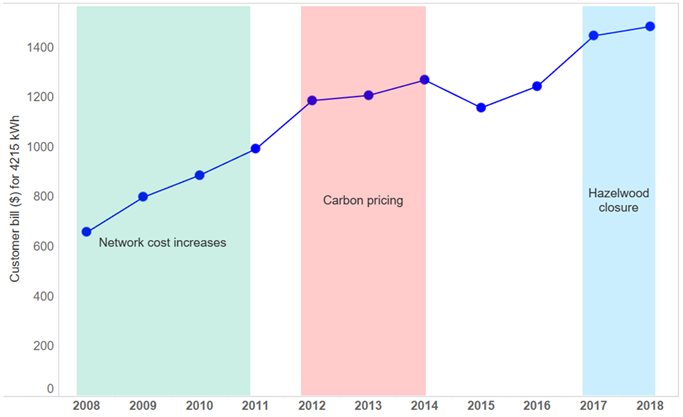

The real motivation for questioning what was going on was that the costs of excess supply were being passed onto consumers in the form of higher prices. We are concerned about high prices today, but in real terms wholesale energy prices at the start of the NEM, at just over $90/MWh, were slightly higher than today’s prices in NSW. The other problem was that the debt used to fund power stations was a drag on the State’s finances, limiting the ability of the government to fund other things. Both outcomes were a consequence of the prevailing institution, regulatory and industry structure.

So in 1987 legislation was passed that required the Electricity Commission of NSW to prepare an Electricity Development and Fuel Sourcing Plan. Each plan was to cover at least 30 years. In 1989 the Electricity Commission of NSW published its first, and as things turned out, its last, 30 year plan.

As someone that played a minor role assisting the inquiry, my first thought when the ink wasn’t yet dry on this plan was “this will never work”. The information requirements were too large, the future far too uncertain and the risks so asymmetric to have really have much confidence that “better planning” would materially reduce the possibility of delivering outcomes much different than what had happened in the past.

One way or another it seemed to me that history was destined to repeat itself. In my mind, if future demands, technology, input costs, policy objectives, and the like were uncertain, asking how to plan better was asking the wrong question – or at least diverting attention from what was the most pertinent question.

Now while the development of more sophisticated and informative analytical techniques that underpin this improved planning is always welcome, the primary question in my mind was how to change the institutional, regulatory and industry structure to deal with what seemed to be really the only certainty – that being, that today’s expectation were bounded to get mugged by tomorrow’s reality – and how do you manage the consequences when that happens?

During this period there was a lot of what some people would refer to as virtue signalling going on. Generally it went along the lines of, private sector – good and efficient, public sector – bad and inefficient.

The proposition that the private sector was necessarily better at foretelling the future than the public sector was it seemed if not preposterous, at least a very shaky foundation for a major structural microeconomic reform.

So the thinking basically went along these lines. What if we can have a competitive wholesale electricity market, which of course had to be designed so that it conformed to the laws of physics but also by definition had to have multiple buyers and sellers? If you simply have a central authority deciding how much capacity will be required in the future and conducting an auction for who would supply it there would be no reason to expect the outcomes to be any different from when we had with the electricity commissions. “Contracting out”, may be the only option for some non-priced public services, but in the energy sector the outcome would be to efficiently build the wrong things at the wrong time and possibly in the wrong place and for the costs of doing being passed onto consumers.

If we could have a competitive wholesale market – in the proper sense of the word “market” - then while the market participants would have to go through the same forecasting and planning processes that the people in the electricity commissions had to do, the consequences when the future turned out to vary from what was expected, would be quite different. For instance, if they over-invested then prices would fall rather than rise.

That is, without having to rely on participants in a competitive market being superior at forecasting the future, by changing the institutional and industry structure, which is really about managing the way in which risks are allocated, the consequences for consumers and the consequences for the economy more generally would be quite different.

But of course it’s that very thing, the change in the allocation of risk, that changes behaviour and drives different sorts of outcomes. And certainly in the case of successful microeconomic reforms – and I’d be the first to admit that many of the total package of microeconomic reforms that were being considered at the time, failed on implementation – but those that did succeed drove more efficient outcomes and higher productivity growth which is a driver of economic growth in the longer-term more generally.

Which is really where the electricity sector reform story fell in line with the broader microeconomic reform agenda – that longer-term economic prosperity had to be underpinned by productivity growth.

Given that we are coming up to the end of the 30 year time horizon of the Electricity Commission of NSW’s 30 year plan, earlier this year I thought it might be a bit of fun to dig it out and have another read.

Viewed from the perspective of the time it’s a highly credible piece of work particularly with the ways the various scenarios of the future were constructed and in many respects might be regarded as “forward-looking” for its time with somewhat familiar topics being discussed – greenhouse gas emissions, demand response, tariff reform – it’s all there.

And of course it’s totally unfair given what we know today, to judge it in hindsight. And to dismiss it would miss the point I’m trying to make. Which in part, is to question the existence, or utility of putting faith in, an omnipresent all-knowing planning god.

I recently described the tendency in the face of uncertainty to centralise decision making as comforting people with the delusion of control over outcomes. In the face of uncertainty centralising decisions concentrates risk.

To help illustrate the point the 30 year plan considered the options for future power stations that were available in NSW. Not all of them would be needed, but the question was what options were available? It identified a range of existing and future sites that could accommodate 48 additional 660 MW units.

By 2020, depending on the scenario, it said that NSW would need somewhere between 12 and 34 additional 660 MW generating units. Over and above the two at Mt Piper, which were under construction at the time. And under the scenario considered most likely NSW would need 20 additional 660 MW units. As compared to the actual number, which we know that we’ve had over that period which is zero.

The world we face today of course is vastly different from the one that existed in the late 1980s and early 1990s. We’re almost on a different planet. One thing although that possibly endures is the underlying need to have a set of policy frameworks in place that drives innovation and productivity growth.

In those earlier times there was a consensus between Governments around that as an objective – they argued about how to do it, and how the benefits and costs would be distributed, but there was a sense of common purpose when it came to the objective.

Of course that contrasts with today’s circumstances where the objectives that governments are pursuing are somewhat contested between themselves. Given we have a national framework dependant on a degree of cooperative federalism that has some real impacts on the outcomes we are experiencing.

And while questions around what are the appropriate institutional, regulatory and industry structures for today and into the future are obviously being discussed and debated it seems rather futile to engage too much in those discussions without there being some consensus on objectives beforehand to guide those discussions. Indeed many of today’s discussions about “market design” seem to be a phony war over the inability to build sufficient agreement about objectives.

One of the interesting things that happened recently, and probably the Governor of the Reserve Bank Philip Lowe, has been the one most reported to have articulated it is, against a backdrop of the limitations on monetary policy and fiscal policy, the emphasis on the need for structural reform, -given that microeconomic reform is an unfashionable term these days. That is the policies and frameworks that will drive innovation and productivity growth.

AEMC key priority areas

In this environment what is it that the AEMC should do, or can do? Given the Commission’s remit, what can we do to address the issues that face the sector, and make our contribution to assisting productivity growth and innovation?

Traditionally the Commission given our statutory role have taken an almost semi-judicial stance. When people put rule change proposals to the AEMC they need to be confident that they will be evaluated on their merits against the national energy objectives.

Given the changes occurring in the sector and the sheer volume of rule changes that are being put to the Commission we have felt it necessary to articulate a set of priorities. Essentially these are issues that are able to be addressed through the national energy rules. They are the areas that in the AEMC’s view will go a long way to addressing many of the concerns that people have with the sector’s performance in this period of history.

I’ll just touch on some aspects of why they are important. Effectively the Commission is asking people to consider rule change proposals that fall within these five buckets, and if they put forward proposals in these areas, the AEMC will want to get onto them as soon as we can.

If people have other rule changes they want to propose they can, and we are obliged to deal with them, but you might have to convince us that our analysis of what are the major issues affecting the sector’s performance is missing something, or just accept that it is going to take second priority. It’s just a pragmatic response; a queuing criteria if you like.

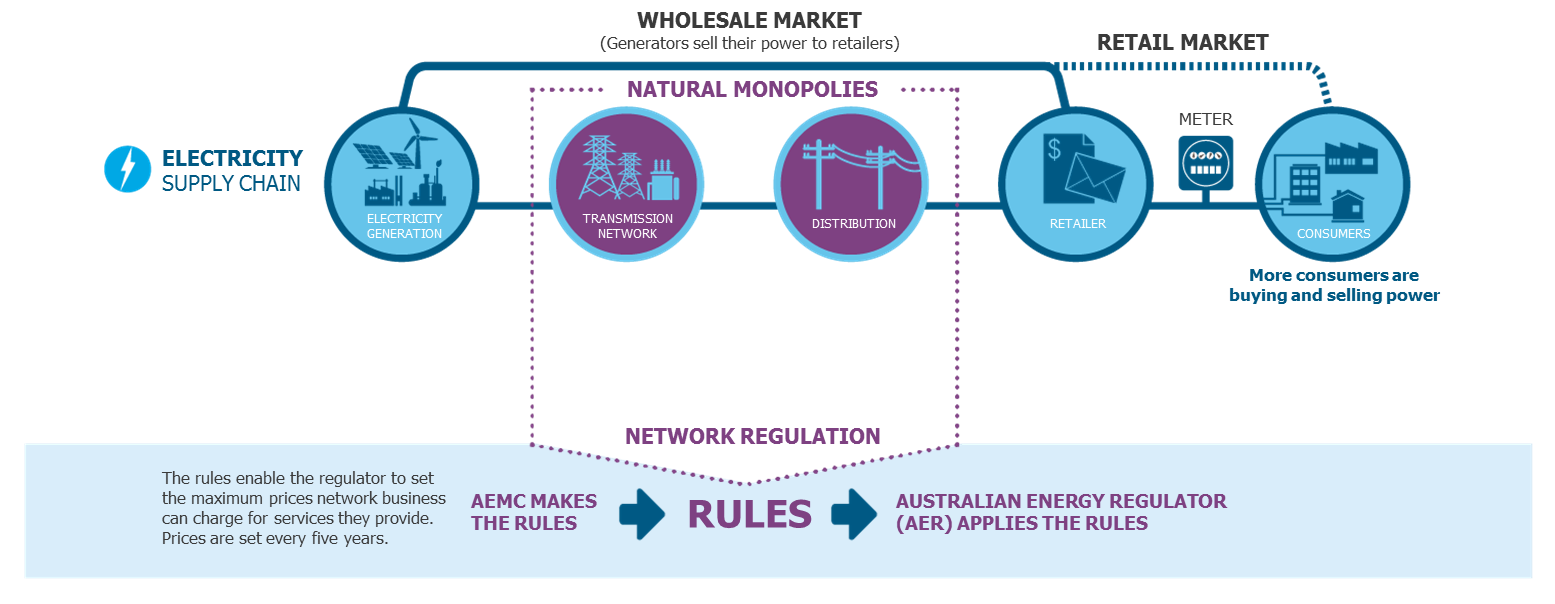

The first is generator access and transmission pricing. Currently generators primarily get access to the transmission system by the way in which they bid into the spot market. The access arrangements are essentially built on the premise that transmission is built to achieve reliability outcomes for consumers, and therefore consumers pay for transmission and transmission revenues are regulated.

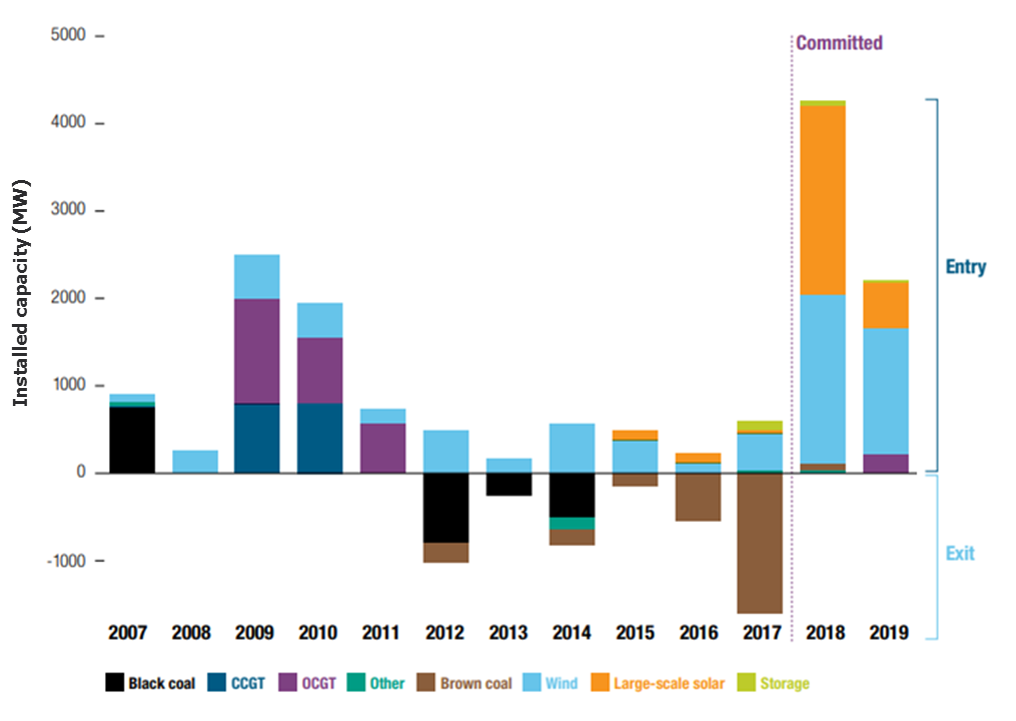

But given that we are moving from a system with a relatively small number of generators in very predictable locations to one more characterised by a larger number of smaller generators that are far more geographically dispersed, there are some people arguing that rather than building transmission for the benefit of customers, we need to build transmission for generators.

It seems reasonable to ask that if that is the case, if that is how you want to construct this, it is reasonable to ask that generators pay at least part of the transmission infrastructure that is required to give them access to the market.

The second priority requires introducing you to a bit of electricity industry speak. In our everyday language security and reliability tends to be seen as meaning the same thing. But in the electricity sector the two are quite different, and accountabilities and responsibilities for managing them are also quite different.

When we talk about system security what we’re talking about is operating the power system within some fairly tightly specified technical variables so the system can be controlled, even when things go wrong, as they do almost daily in a system as large and complex as ours. The responsibility for keeping the system in secure operating state primarily rests with the operator, the Australian Energy Market Operator, but also there’s a role for the transmission network operators.

It’s a very technical set of variables that need to be managed. A power system needs more than MW and MWh to operate successfully and a lot of those technical characteristics effectively used to come for free as a by-product of the energy produced by coal and gas-fired power stations just by the nature of their physics.

The newer technologies don’t have the same physical characteristics and a lot of these services don’t come as a by-product of producing energy. We have what Professor Paul Simshauser once referred to as missing or partial markets problem.

There are things that the power system need that are not explicitly valued at this point in time so we need to find a way of valuing them or regulating for them.

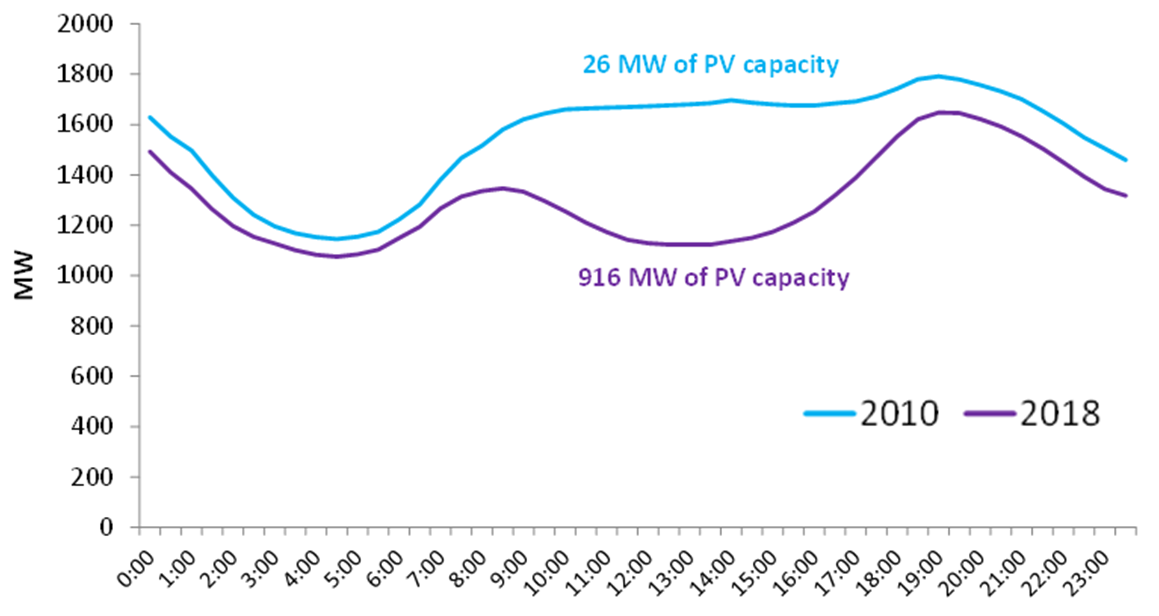

I’m sure you’re very familiar with the phenomenal penetration of distributed energy resources, most notably solar PV on people’s houses. And when you have a small amount of this stuff it’s not a problem for the main power system, but given the levels of penetration, particularly here in Queensland and in South Australia, the way in which they operate has a flow-on effect back to the rest of the network.

There are parts of the South Australian network for instance where at particular times of the day the load is negative, i.e. where the PV in that part of the network is actually producing more than anyone is consuming behind those parts of the system. Knowing what these distributed energy resources are doing is an increasingly important part of maintaining a stable system.

The integration of distributed energy resources is a vital reform so that their owners not only can get the best value for the energy and network services they offer but by utilising them in the most efficient way, everyone benefits from more efficient distribution networks.

The digitalisation of energy supply is where a lot of innovation is happening and can happen at the retail level. Enabled by this technology, a very different notion of what it means to be in the retail space in the energy sector emerges. We’re starting to refer to it as the retail energy services sector.

The way I think about it is by reference to the ripple controlled hot water systems that I grew up with. I didn’t care when the energy went in, just cared that when I got up in the morning I had a hot shower. The nature of the technology these days enables essentially the same sort of model to be applied to a whole bunch of energy consuming appliances, i.e. the service you get is the service that you want, but how energy is used can be more actively managed.

The final priority is reliability. One of the things that made the energy market work, particularly during those periods of time when people thought it worked well, was a very close alignment between the financial incentives that market participants face and the physical needs of the system at any point in time.

Did a reliable power system need investment in generation that would meet demand for 80 per cent of the day, 40 per cent of the day, five per cent of the day, or for a few hours on a few days during summer? The price signals in the spot and contract markets conveyed that sort of information and market participants responded to it. As much as you can ever judge these sorts of things, market participants basically invested in the right sort of kit at the right time at the right place.

One of the consequences of some mechanisms used by governments to achieve policy objectives related to renewables, which by their nature are usually intermittent, weather dependent sources of supply, has been delinking of the financial incentives faced by those investing in and operating these resources and physically what the system needs at any point in time.

If you get the same revenue for producing energy at 3 o’clock in the morning in May and at 3 o’clock in the afternoon on a Thursday in February, then the link between what the system needs and the financial incentive to be available when the system needs you the most ends up being broken.

This is of course not a comment on government’s policy objectives, which is entirely for them to decide. Rather it’s simply to point out that the mechanism used to achieve them is important when you are dealing with something with interdependencies like the power system.

One of the premises of what was the National Energy Guarantee and what is the Retailer Reliability Obligation mechanism is to re-establish these links.

The recent deal Infigen did in putting a portfolio together of intermittent sources of generation and a gas turbine is exactly the sort of arrangements that we would hope to incentivise through the Retailer Reliability Obligation.

It provides additional capacity to offer contracts against the portfolio and it’s the nature of those contracts that creates the link between a reliable power system and the financial incentives faced by Infigen.

Conclusion

I will conclude with what is unashamedly a plug. We have a very unique, not just in Australia but internationally, set of arrangements for changing the regulatory arrangements in response to either changes in policy or real changes happening on the ground.

Traditionally if you’re dealing with a single jurisdiction, or in places like the United States or other federations you have a set of legislation which empowers government itself and/or a government authority to determine the regulations that sit beneath it.

We of course have energy laws, which have been adopted by all the relevant NEM jurisdictions and national electricity, gas and retail rules.

Instead of requiring nine governments to agree to any changes in the rules, that was always seen as being a bit difficult to achieve, its predecessors and the AEMC were established with the delegated authority to make what are effectively regulations. The then question became who gets to propose changes to the rules?

What was decided was… anybody can – except the AEMC itself. I sometimes get asked would I like to be able to just change the rules myself? To which my response is, while I would trust myself with that power I wouldn’t trust anybody else.

So anybody, quite literally anybody – and we have had everyone from private citizens through to the Commonwealth Government propose rule changes – can formally propose rule changes as a way of improving how the sector is regulated. The AEMC’s obligation is to evaluate them against statutory objectives which speak to the long term interested of consumers with respect to price, security, reliability, etc.

So the point being, you do not need to look solely to government to come up with ideas about how to improve the way this sector operates or is regulated. The arrangements for changing the rules, while in some respects a by-product of our particular federal structure, have built within them the premise that the people who are directly involved in the sector – be they market participants, be they interested organisations or other market institutions, be they consumers – are probably going to have a much better idea of what the issues on the ground are and ideas for how to address them.

And they have the ability to come forward and put those ideas directly to the Commission and have them evaluated against the statutory objectives set by governments.

We get rule changes quite literally from everybody. You are in just as good a position as anybody else to initiate a process to get them changed.

This process has described this as “open source” regulation making.

As long as the statutory objectives are clear, and as long as the body evaluating them can be held to account through the courts to evaluate then against policy objectives embedded in statutory obligations, we have a structure that welcomes ideas coming forward from people like you.

It means you have a direct path to change how this sector operates. The opportunity to improve outcomes for consumers through changes in the rules is very much in your hands.